A Tale that Doesn’t Withstand Critical Scrutiny

It’s no longer out-of-bounds to wonder if Jesus existed

In his book, Outgrowing Religion, John Compere wrote: “The myth of Paul Bunyan makes a good story, as does the story of Jesus. But neither tale withstands critical scrutiny or gives us a clue about the meaning of life. For that, we have brains.” It can be noted, by the way, that legions of New Testament scholars have applied plenty of brainpower to analysis of the four gospels—and they know very well that these stories do not withstand critical scrutiny. Of course, to defend the faith at all costs, evangelical scholars hold out against this conclusion. But Jesus studies have been in turmoil for decades because scholars have not succeeded in identifying which parts of the gospels actually qualify as history. No agreed-upon methodology for that has been discovered.

All of this turmoil has gone on “behind closed doors,” so to speak: the vast majority of the laity are unaware of the distress in Jesus studies. The clergy, of course, have a vested interest in keeping this scholarly angst about Jesus out of sight. They have a lord and savior to promote, and want their congregations to accept Jesus “as is” in the gospels; from the pulpit they recite the stories that inspire awe and belief. No matter that the stories may not the historical at all!

The angst has been taken to new levels in recent years by scholars who have advanced arguments that Jesus may never have existed. When laypeople hear about this, they dismiss such thinking as the work of crackpots or malignant atheists. After all: the gospels! How could the gospels get it all so wrong? But here’s the irony: these four early Christian documents themselves fuel the suspicion that the Jesus story is fake, or—to put it less bluntly—it is theologically motivated fiction. Randell Helms wrote his book Gospel Fictions in 1988, and he followed in long tradition of doubting these “sacred” stories.

Christian gloating is misplaced, as David Fitzgerald points out:

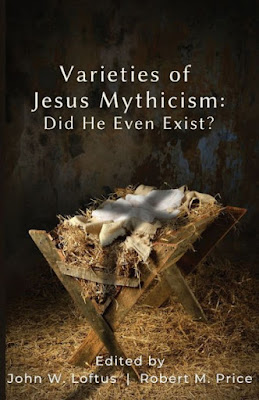

“Christians love to crow that virtually all historians believe Jesus existed; they conveniently ignore the fact that no non-Christian historians believe their Jesus existed. In fact, the level of disagreement among Jesus scholars over the most basic facts concerning him is astounding. Of course, first comes the divide between ‘the Jesus of faith’ and the ‘Historical Jesus’—and both are simply placeholders for the entire family trees of hypothetical, reconstructed Jesuses.” (p. 11, Varieties of Jesus Mythicism: Did He Even Exist? eds, John W. Loftus and Robert M. Price)

Indeed, this is the state of Jesus studies, and has been for a while. Laypeople get some reassurance when they hear New Testament scholars dismiss Jesus-Mythicism as nonsense. But how is Mythicism fueled? Damn: the New Testament itself raises suspicion that the Jesus story was invented: it evolved over decades to meet the needs of the early Jesus cult. My advice to Christian friends is rise to the challenge of studying the issues, without flaming out. The study of Christian origins is a sobering business.

Just a little bit of digging will reveal that the scholars who argue the mythicist case are not frauds or crackpots. Look up their writings, e.g., Richard Carrier, David Fitzgerald, Earl Doherty, Raphael Lataster, and Robert Price. Indeed, Carrier is one of the top Jesus scholars of our time. And now we have a new resource, the recently published anthology edited by John W. Loftus and Robert M. Price, which I just quoted from, Varieties of Jesus Mythicism: Did He Even Exist? Many Christians may feel quite uneasy picking up this book, because they already have their suspicions that all is not right in the gospel stories. Sure, we’re supposed to believe that Jesus turned water into wine—sometimes walked on water! —and floated up and away through the clouds at the end of the story. Believers who have a pretty good sense of how the world works are uneasy with these stories—no matter the appeal of priests and preachers to “just believe”! Well, if these stories are creative fictions…what does that suggest about the whole Jesus story?

This anthology has sixteen essays written from different perspectives on the topic. Robert Price advises in the introduction: “It’s worth the mental effort to grasp and weigh each one.” (p.7)

Chapter One was written by David Fitzgerald (author of four books presenting the case for mythicism), titled Why Mythicism Matters, or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Jesus (Myth Theory). In this 22-page essay Fitzgerald discusses seven reasons why mythicism matters, and he covers fundamental issues that believers need to know. This essay is a fine introduction to the topic. I want to draw attention to a few of Fitzgerald’s key points.

What are the consequences of the ecclesiastical establishment dominating the conversation for hundreds of years? A real Jesus is firmly embedded in our collective psyche—and there is fierce determination to keep it that way. In his book, The End of Biblical Studies, Hector Avalos pointed out that “the majority of biblical scholars in academia are primarily concerned with maintaining the value of the Bible despite the fact that the important questions about its origins have been answered or cannot be answered. More importantly…academia, despite claims to independence, is still part of an ecclesial-academic complex that collaborates with a competitive media industry.” (p. 15)

Fitzgerald drives home this point brilliantly under his Fifth Reason (i.e., why mythicism matters): That One Slight Problem with Biblical Studies. Luther boasted in a famous hymn that the Christian god was a “mighty fortress”—but the same applies to Christian academia, represented by thousands of seminaries worldwide (according to Wikipedia, there are 6,974 Catholic seminaries alone). In research for one of his books, Fitzgerald reports the finding that “at least two-thirds of all religiously affiliated schools required their teachers to tow a strict theological line…so perhaps the question shouldn’t be, ‘How many biblical scholars reject myth theory?’ but, ‘How many biblical scholars are contractually obligated to reject myth theory?’” (p. 25) The ecclesial-academic complex doesn’t want anybody messing with Jesus.

“…in the rarified world of biblical studies, Christian presuppositions, biases, and above all, theological (and their accompanying financial) interests still hold sway, making life very hard for any scholar whose findings threated Christian doctrine.” (p. 24) For these scholars, looking directly at Jesus myth theory—candidly facing the troublesome evidence for it in the New Testament itself—is too much like staring at the sun: “Please don’t make us do that!” Fitzgerald includes a quote from Upton Sinclair, “It is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends on his not understanding it.” (pp. 25-26) It is no surprise whatever that Jesus myth theory has failed to gain traction in an academic environment that operates under heavy faith bias.

Fitzgerald’s Reason Three,“But the Evidence…” gets to the heart of the matter: The gospels seem to weigh heavily against any suggestion that Jesus didn’t exist. After all, these famous accounts have been venerated for centuries: why doubt that they’re true? John chapter 8 presents a case study of one of the problems. In this chapter we find the story of a woman, caught in the act of adultery, dragged before Jesus. This prompted his famous reprimand: “Let the one who is without sin throw the first stone.” We now know, however, that this story was not in the original manuscript of John’s gospel; indeed, in some NT manuscripts, it found a place at the end of Luke 21. Which prompts the question, of course: where did this story come from? We have no clue where it may have originated, and have no way at all to verify that it is an authentic story about Jesus.

But, unfortunately, the same can be asked about all the stories in the gospels: where did they come from? Devout New Testament scholars have long advocated ways to somehow anchor the gospel stories to history, e.g., the gospel accounts are based on eyewitness accounts, or “reliable” oral tradition, or theoretical “sources” that no longer exist (the Q document is a big favorite). These are all unverified, however, i.e., there is no contemporaneous documentation to back up these claims. These are guesses and speculations of devout scholars, designed to pull the gospel accounts back into the realm of history.

Here’s the barrier that Fitzgerald identifies: “All these gospel authors are anonymous, writing at least a generation or more after the fact. None claims to be eyewitnesses; on the contrary, ‘Luke’ explicitly tells us he is investigating the story inherited by his generation of believers…” (p. 17) “As their actual identities are completely unknown, we have no other literature or scholarship to their credit that we can test for their skills and accuracy. Far from being objective, dispassionate historians, all freely declare their bias toward persuading new converts.” (p. 18)

It is so commonly accepted in Christian circles—among the laity and in academia—that the gospels are evidence. But close scrutiny of these texts shows that this is a spurious claim. Fitzgerald offers the correct challenge:

“What we should be doing before we claim any fact of Jesus’ life has been accepted with an acceptable level of certainty is to begin with two simple questions: What is the source for any claim about Jesus, and how reliable is that source? Otherwise, which camp is operating under dogma and wishful thinking: the mythicists, or the Historicists? After all, it has become undeniably apparent to everyone but the most hidebound believers that—historical Jesus or no—our gospels are myths about Jesus. The question remains: are they myth all the way down?” (pp. 20-21)

Randel Helms prompted suspicion in his 1988 book: “Each of the four canonical Gospels is religious proclamation in the form of a largely fictional narrative. Christians have never been reluctant to write fiction about Jesus, and we must remember that our four canonical Gospels are only the cream of a large and varied literature.” (p. 11, Gospel Fictions)

A largely fictional narrative. The burden of proof is on devout scholars: come up with fool-proof ways to tell the difference between history and fiction in the gospels. So far that hasn’t happened; these documents favor religious proclamation.

Fitzgerald also points out how the problem is compounded by what happened to the four gospels—another major weakness in the assumption that the gospels can be taken as evidence: we don’t know what the gospel authors actually wrote. All of the original manuscripts vanished. What a disaster—and it’s a mystery why a watchful deity would have allowed this to happen. Fitzgerald describes the clumsy process:

“It’s not until the late second/early third century that we begin to get the complete texts of some of the individual books of the New Testament, and not until the early-to-mid fourth century that we have our complete New Testaments, the Codex Vaticanus and the Codex Siniaticus…This means for the first 150 to 200 years of Christianity, we have a complete textual back-out period, where we simply cannot know what was originally written about Jesus at all.” (pp. 18-19) And we do know that scribes made thousands of errors in the copying process. How many of the laity are even aware that this is how they ended up with the Bible?

I urge readers to reflect deeply on the Seven Reasons that Fitzgerald describes. “The truth is,” he states, “the majority of biblical historians are just as wrong about there being a Jesus as they are about there being a god. And for the same reason.” This is the challenge we put to theists: “Please show us where we can find reliable, verifiable data about god(s)—and all theists must agree: Yes, that’s where to find it.” We put the same challenge to faith-biased Jesus scholars: “Please show us where we can find reliable, verifiable data about Jesus—and all devout scholar must agree: Yes, these are the historical bits in the gospels.”

Fitzgerald has identified the problem: “We should not forget that the field of Jesus Studies is in crisis because Christianity is in crisis. Both are under tremendous pressure to show that all is well and under control, even while their evidentiary foundations are crumbing.” (p. 26)

David Madison was a pastor in the Methodist Church for nine years, and has a PhD in Biblical Studies from Boston University. He is the author of two books, Ten Tough Problems in Christian Thought and Belief: a Minister-Turned-Atheist Shows Why You Should Ditch the Faith (2016; 2018 Foreword by John Loftus) and Ten Things Christians Wish Jesus Hadn’t Taught: And Other Reasons to Question His Words (2021). He has written for the Debunking Christian Blog since 2016.

The Cure-for-Christianity Library©, now with more than 500 titles, is here. A brief video explanation of the Library is here.

Please support us at DC by commenting on and by sharing our posts, or subscribing, donating, or buying our books at Amazon.

0 comments:

Post a Comment