Is It Possible Your Minister/Priest Doesn’t Believe in God?

What might have caused that to happen?

Here’s a sensational headline that would shock the world: Pope Resigns, Issuing a Statement that He No Longer Believes in God. But we’ll never see such a headline because, even if a pope stepped down because of nonbelief, the Vatican hierarchy wouldn’t allow such honesty. Other more palatable reasons would be given. I once asked a prominent Italian television journalist if it could possibly be true that the Vatican clergy really believed the theology-on-steroids that the church promotes, e.g. such wackiness as transubstantiation, the immaculate conception, Mary’s bodily assumption into heaven. He responded, “Oh, maybe half of them do. But don’t forget, it’s a business.”

The church thrives on the promotion of unevidenced dogmas—and it’s not about to stop. But is a disbelieving pope farfetched? Even a brain that has been trapped by religion for decades is not immune to sudden, devastating insights. A few years ago, following an earthquake in central Italy that killed hundreds, the pope assured Catholics that Jesus and his mother were present with the survivors to “offer comfort.” Might it have occurred to him that Jesus and his mother, representing an all-powerful god, failed to show up to prevent the earthquake? Being there for “comfort” afterwards seems too anemic. How many times do tragedies have to happen before the incoherence sinks in and shatters faith? The church celebrates the countless appearances of the virgin Mary to the faithful worldwide, but we wonder why she doesn’t show up in the room when priests rape children, screaming at them to stop. This criminal activity, unrestrained by an all-knowing god, adds to the incoherence of faith. Surely even cardinals and popes have stopped to wonder why their god’s power is deficient at crucial moments.

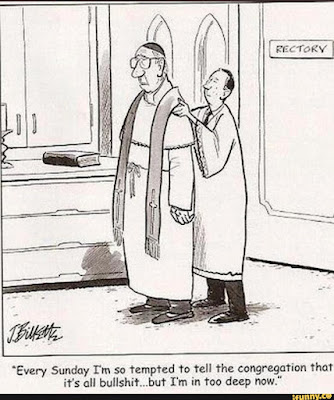

The realities of the world we live in constantly erode religious claims. And the clergy can be plagued by doubt as much as anyone else—whether it’s a pope or the ministers/priests who serve churches anywhere in the world. And it’s just a fact that many ordained clergy, despite their devout upbringing and years of seminary training, cannot sustain the faith. They no longer believe, and whisper to themselves, “I am an atheist.” Maybe even after ten or twenty years in the ministry or priesthood. Continuing with their duties becomes agony, especially the worship services. This cartoon by John Billette reflects their dilemma. Unknown numbers are clergy, who truly are “in too deep,” are trying to escape.

This phenomenon has been researched/studied extensively, and the findings summarized in the 2013 book by Daniel C. Dennett and Linda LaScola, Caught in the Pulpit: Leaving Belief Behind.

Richard Dawkins wrote in the Foreword:

“It is hard not to feel sympathy for those men and women caught in the pulpit. It is for this reason that a group of us set up The Clergy Project. I originally even thought of trying to raise money for scholarships [for retraining clergy]…That proved too expensive. But we did provide apostate clergy with a website where they can secretly go to talk to each other, in confidence, protected from parishioners and even from family by pseudonyms and passwords: a safe haven where they can share experiences, advice, even metaphorical shoulders to cry on. Dan Dennett and Linda LaScola were involved in The Clergy Project from the start: indeed it was largely inspired by their pilot study, together with the experiences of the pioneer apostate Dan Barker.”

More about this book shortly. The Clergy Project was founded in 2011, and now has more than 1,200 members. It provides a way, especially for clergy who are still serving churches, to try to find their way out. The obstacles can be daunting, when the education and experience of many clergy don’t match the needs of jobs in the business world. Considerable reinvention is required, usually while dealing with stress on several levels.

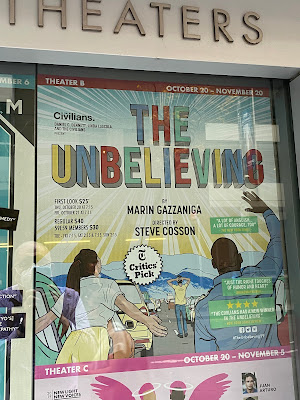

These frustrations come alive in a new play about the inception of The Clergy Project, The Unbelieving, written by Marin Gazzaniga, currently on stage at the 59E59 Theatre in New York City. The current run is limited, ending on 19 November. Linda LaScola, co-author of Caught in the Pulpit, interviewed many clergy who were going through this agony of failed faith. In many cases, this meant that their whole world was collapsing. The transcripts of these interviews were used by Marin Gazzaniga in creating the script for the play. Thus to watch the play is, in a very real sense, a matter of witnessing the pain of the characters real-time.

This is a high-impact theatrical experience.

One of the characters is a nun, who served as a nurse in a mental hospital before important medications had been invented. She was distraught by the intense suffering she witnessed. How could this be if there is a good god watching out for us all? She reflected on the Michelangelo image of god stretching out his hand to touch the hand of Adam. This gesture of intimacy has intense appeal, of course, but why is it missing in the real world of egregious suffering? Why does mental illness even exist if god cares—if he notices when a sparrow falls to the ground? Mental illness scuttles the claim that human bodies are intelligently designed by a benevolent creator. How can our brains break down so severely? This in an example of horrendous suffering that undermines god-is-good theology. So, for the nun, this incoherence played a major part in the erosion of her faith.

New York Times reviewer Laura Collins-Hughes praised the play. She highlighted this example especially:

“For Adam, not his real name, change started with curiosity and critical thinking. A Church of Christ minister and a creationist, he came to realize that his worldview was sheltered, so he set out to educate himself.”

“In nine months, I read over 60 books, listened to hundreds of hours of lectures and debates, watched 25 documentaries and movies,” he says. “Went through eight online courses on philosophy, evolution.”

“It didn’t occur to him that what he found would shake his faith. He thought, he tells a researcher, that God ‘can handle any questions I’ve got.’”

“‘Well, he didn’t measure up!’ says Adam [played by David Aaron Baker], his voice rising with emotion that’s more wounded than angry. His belief in God has left him, and that threatens his job, his family, his friendships — every corner of his life. So when he speaks to the researcher, he insists on the protection of a pseudonym. He cannot afford for word to get out.”

Collins-Hughes observes as well:

“‘The Unbelieving,’ a probing, interview-based new play from The Civilians, is about people like Adam: current and former members of the clergy who have lost their religion, even if they still publicly practice it.”

“…this smart and slender play listens to its characters without judgment. Not trying to hit its audience over the head with lessons, it is conducive to empathy.”

“There’s a lot of anguish in ‘The Unbelieving.’ As it turns out, there’s a lot of courage, too.”

As I noted earlier, the play has a short run in New York, and I’m not sure when it will be published for purchase, but Caught in the Pulpit: Leaving Belief Behind remains the essential text for studying the issue. At the outset, the authors explain the origin of the study (“What We Did and Why We Did It), before presenting five sketches of people that they studied, including Presbyterian, Lutheran, Catholic, and Mormon clergy. Loss of faith can come about in various ways, as these five sketches illustrate. But a common theme is discovering information about their religions that usually emerge only after careful study.

In the profile of the Mormon bishop, for example, we learn that on-line information was crucial:

“I think the Internet was a big factor, just beginning to research some of the questions about my faith and its origins. You know how you’re on the Internet and something strikes your eye? You say, ‘Oh, that’s kind of interesting. I’ll just check that out—I’ll just kind of browse.’ So I began to read some articles of an unorthodox nature that began to cause me to expand my perspective a little bit and help me to see things from a different point of view. I’ve always tried to be an open-minded person, so I began to see things from a different side.” (pp. 58-59, Kindle)

“I was always taught that Joseph Smith had these gold plates and he had a tool to translate them with a scribe. Well, I come to find out that’s not really how it happened. How it happened is, the gold plates aren’t even there, or they’re covered up in some way. He’s got a hat, with what’s called a seer stone, that he previously used to go treasure hunting with. He’s got that in the hat, he’s looking in the hat, and then this kind of dictating is coming to him. So I’m wondering, ‘What’s the purpose of the gold plates, then. Right?’” (p. 58, Kindle)

One of the most interesting sections of the book is titled, “Three Seminary Professors.” We learn that one of the problems they face is the naiveté of incoming students, who are highly motivated to serve their god—but careful, critical, skeptical analysis of Bible texts has been missing in their religious cultivation. So they’re shocked to learn what Bible scholars have discovered over the many decades of careful analysis, e.g., Moses didn’t write the Pentateuch, there is no evidence that the Israelites escaped from Egypt, the Jesus birth stories in Matthew and Luke are fictitious. Here, in fact, some of the seeds of doubt in the long run are planted.

And these seminary graduates encounter resistance to learning when they move on to their appointments as pastors, as Dennett and LaScola note:

“For most of our participants, applying their seminary-acquired knowledge meant working in a congregation. It was in this setting—in the pulpit, in study groups, in one-on-one meetings—that these freshly-minted clergy brought their theological knowledge to bear and practiced their pastoral skills. It was here that they met with troubling experiences they ultimately could not reconcile. Many of our participants found that the people in the pews not only were uninterested in their pastor’s advanced knowledge but actually eschewed it, instead favoring the naïve, feel-good aspects of faith.” (p. 112-113, Kindle, emphasis added)

Too many parishioners are content not to think about the faith; curiosity is not encouraged, which accounts for the ongoing success of the church. Adam—as mentioned above in the New York Times review—provides as example that alarms the church: he read sixty books in nine months, took eight online courses about philosophy and evolution. His conclusion was that god didn’t measure up and he abandoned his faith.

I mentioned earlier examples of incoherence in Christian theology, and we are not at all surprised when we study Christian origins in the first century. Virgin births of heroes and sons of gods were taken for granted in other religions, thus the attachment of this concept to the Jesus narrative is no surprise. There were other dying-and-rising savior cults, and Christianity welcomed portraying Jesus in this way. The purported teachings of Jesus—which I call Jesus-script because that is what the gospel authors wrote—have far too much that is alarming and offensive (see the list at BadThingsJesusTaught.com).

During a talkback session at the performance of The Unbelieving that I attended, Linda LaScola said that she’s not opposed to religion—but she is against religious indoctrination. Humans have been fighting about religions for thousands of years, and have resisted learning about religion—because of indoctrination. Caught in the Pulpit provides yet more evidence of the harm done.

David Madison was a pastor in the Methodist Church for nine years, and has a PhD in Biblical Studies from Boston University. He is the author of two books, Ten Tough Problems in Christian Thought and Belief: a Minister-Turned-Atheist Shows Why You Should Ditch the Faith (2016; 2018 Foreword by John Loftus) and Ten Things Christians Wish Jesus Hadn’t Taught: And Other Reasons to Question His Words (2021). His YouTube channel is here. He has written for the Debunking Christianity Blog since 2016.

The Cure-for-Christianity Library©, now with more than 500 titles, is here. A brief video explanation of the Library is here.

Please support us at DC by commenting on and by sharing our posts, or subscribing, donating, or buying our books at Amazon.

0 comments:

Post a Comment