And now we have a handy guidebook!

In recent days, Pat Robertson came out of the woodwork—or rather, out of retirement at 91—to explain to the world that Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine is part of God’s plan to hasten the End Times, in a battle that will ultimately play out in Israel. What? We can be sure that Christians throughout the world condemn Putin’s aggression, and are appalled by the suffering caused by the ongoing invasion. Where did Robertson come up with this crazy idea? Well, it comes right out of the New Testament, even in the bad theology we find in Jesus-script: the coming of the kingdom of God—the End Times—will bring as much suffering as the world experienced at the time of Noah. Part of Robertson’s delusion is his conviction that he knows God’s mind well enough to coach the rest of us.

Our first impulse may be to say, “What an idiot!” But is that the case? And am I right in calling him delusional? On the contrary, it seems that Robertson is a shrewd business man. His Wikipedia profile cites his net worth at over $200 million—maybe as much as a billion. He’s clever enough to play to his audience, which savors predictions about disasters (God is going to get even!) and The End Times. But to those outside his chosen—and carefully cultivated audience—his predictions just sound wacky. So it’s not a stretch to say that his brand of Christianity makes him talk like an idiot.

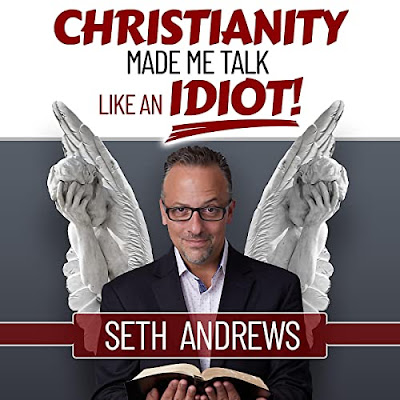

How does this happen? Is this something that sabotages all Christian brands? Seth Andrews discusses this phenomenon in his new book, Christianity Made Me Talk Like an Idiot! It’s up-close-and-personal

for Andrews because he was raised in an evangelical Christian family. Only after he had escaped from this insular understanding of the world did he grasp how much he had talked like an idiot (That escape story is told in his 2012 book, Deconverted: A Journey from Religion to Reason). Christianity—no matter which brand—is still anchored to ancient superstitions, no matter how much apologists try to disguise this fact. You can’t endorse and advocate the basics of Christian theology without talking like an idiot, since this theology is extracted from concepts of the world that we now know to be false, naïve, detached from reality.

Andrews is careful, however, to make a distinction between being an idiot and talking like one:

“No, Christians aren’t idiots, at least no more than the average person. I was a devout Christian for thirty years, and I wasn’t unintelligent, nor did my IQ change when my religious label changed. I considered myself thoughtful, moral, reasonable, and at least as smart as the average person. In other words, I wasn’t an idiot. Yet strangely, I often sounded like one.”

His new book is highly readable—as one would expect of a superb communicator—and provides razor-sharp critique of quite a few aspects of Christian thought, divided into fourteen chapters. The fifteen chapter is titled, Reflection—Pointing the Finger Back at Myself. Please take a quick tour of all the chapter titles via the “Look Inside” feature on Amazon. It is, in fact, an entertaining as well as informative read. Having been immersed in conservative Christianity for thirty years, Andrews has substantial expertise upon which to base his analysis.

I found myself cheering through all these chapters, but here I can focus on just a few of Andrews’ points. I’ll mention three that resonated with me especially.

I suppose one of the greatest irritants, as I try to engage Christians in discussion of their faith, is their substandard knowledge of the Bible. They (supposedly) cherish it as God’s word, so would it not, by virtue of that status, be read and studied obsessively? Instead of watching a movie, how about reading Paul’s Letter to the Romans to discover God’s wisdom for us there? Sad to say, this rarely happens, and Andrews addresses this shallow grasp of the Bible in his Chapter 6, “Hell If I know—When Christians Don’t Know Their Bibles.”

He describes his discovery of Christian ignorance of their scripture by selecting really horrible stories in the Bible, but presenting them to devout readers as excerpts from the Qur’an. Of course, they have no use for Islam, and are scandalized by these accounts of divine cruelty. But then Andrews lets them know these are Bible stories:

“The reactions are almost always the same: disbelief, then denial. The instant and appropriate outrage against the perceived Quranic tales morphs into a litany of excuses and equivocations. It was a different time. The Lord had to be stricter in those days. The story is not literal but parable.” (p. 67)

The distressing stories that Andrews disguised as Qur’an excerpts were all from the Old Testament, so he sometimes hears, “That was the Old Testament, which was replaced by the New Testament. My God is a loving God.” (p. 67) So, okay, that means we can skip the Ten Commandments? Oh, not at all! On several occasions, Andrews has offered $50 on the spot if the Christian he’s addressing can name seven of the Ten Commandments. He hasn’t yet lost the $50. “American Christians believe, but they do not know. How can the list of Ten Commandments be critically necessary for a moral life if its champions live in ignorance of them?” (p. 69)

Of course, the dodge, “But that’s the Old Testament,” doesn’t work at all if Christians know the Sermon on the Mount, which includes Jesus’ blanket endorsement of the old law: “Do not think that I have come to abolish the law or the prophets; I have come not to abolish but to fulfill. For truly I tell you, until heaven and earth pass away, not one letter, not one stroke of a letter, will pass from the law until all is accomplished.” (Matthew 5:17-18)

One of the especially fun parts of this Andrews chapter is his fantasy about a TV quiz show called, “Hell If I Know,” in which he would pepper devout contestants with basic questions about Bible characters. Soon they would “beg to forfeit” when they are “confronted with the parts of their beloved Bible that didn’t sound like a misty Christian radio lyric.” This quiz show would reveal how much Christians don’t know about the Bible, and “…they don’t really want to know.” (p. 70) I’ve run into a couple of Christians in recent years who should be on this quiz show: the one who was enraged when I asked for an explanation of Luke 14:26, the hate-your-family Jesus quote. There could be no such verse, this person said: I was lying! And the other who was puzzled when I mentioned the expected return of Jesus: “I didn’t know he was supposed to come back.”

Chapter 4 of the book is titled, “Eat Jesus—the Creepy, Culty Ritual of Communion”—and one line especially gave me a good laugh. Andrews says that, as a kid he looked forward with “real excitement” to Communion Sunday: “…I am still not sure if my enthusiasm was about being served a thimble-sized glass of Welch’s grape juice and a saltine, or if it was relief that the overlong sermon would end a few minutes early.” (p. 47) Sermons were torture, so that was precisely why I liked Communion Sunday! It didn’t dawn on me until many years later that this was a bizarre ritual—pretending to eat a god and drink its blood. There was no one at the time to tap me on the shoulder and say, “That’s pretty gross, you know.”

Both Andrews and I, as adults, accepted the ritual as essential to Christian piety. For him, “…perhaps communion served to fortify me against the forces of evil.” (p. 47) But there came a time when common sense came into play, i.e., the ability to cast an objective eye on the practice and grasp the strangeness of it all:

“Christian congregations are untroubled by standing to their feet, raising a glass of pretend plasma, waiting for the pastor to say drink up, and ghoulishly knocking back some flavored Jesus.” But then this is crucial: “Would they be so eager to engage if the juice and crackers represented the blood and body of Allah, Krishna, or Zeus, or would the devout consider communion ridiculous and macabre in those other contexts?” (p. 48)

Pretend plasma. Of course, that’s bad enough, but Protestants are happy with the belief that they’re eating and drinking symbolically. Andrews digs deeper in this chapter into what Catholics claim happens: “Catholicism does ramp up the freak factor on many fronts.” (p. 48) How can transubstantiation really be a thing? Andrews reports his research into a couple of Catholic sources, which proved highly unsatisfactory in terms of logical explanations; theologians specialize in theobabble, none of which is falsifiable. Whether on the Catholic or Protestant side of the street, does it make any difference? “The edibles can be symbolic or deemed miraculously real, but the ritual remains yet another creepy example of how superstitions encourage batshittery in otherwise reasonable people.” (p. 52)

Batshittery in otherwise reasonable people. A stunning example of batshittery is the Christian apologetics industry. Here we find scholars and academics—as well as priests and pastors—who have intense emotional attachments to the beliefs of an ancient cult. Unceasingly they write, teach, preach, and lecture to defend their beliefs from rational assaults. Andrews addresses this phenomenon in his Chapter 7, titled, “Explain It to Me—the Calamity of Christian Apologetics.” The undermining irony, of course, is that apologists don’t agree with each other! There are Catholic apologists—their brand of the faith is the right one—opposed to Southern Baptists who are confident that Catholicism is aberrant Christianity. Or as Andrews puts it, “…watch Christianity’s experts transform into a thunder-dome of disagreement on the fundamentals. These people can’t even agree on a proper Bible translation.” (p. 79)

“Watch the armies of seminary graduates and PhDs clash daily on the basics of Christianity [Andrews lists twelve of them]…Sit fifty apologists at a coffee table and ask them to explain and agree on details like these, and they might die of old age in their chairs before ever coming to agreement…” (pp. 80-81)

One of the huge flaws in Christian theology is that its god inspired a book to communicate multiple (and conflicting) messages to the world at a time when a huge percentage of the population was illiterate. How was that supposed to work? Then, of course, over the course of centuries, there has been endless disagreement about what the Bible means, which has prompted so many “experts” to write so many conflicting interpretations.

Andrews takes devastating aim at this practice as well: “…there are countless theology books that examine and explain the Bible, which is ridiculous. If God needs apologetics books to explain his nature and his will, the implication is that the billions of humans who existed before their publication were essentially screwed. How could they properly know God? They didn’t have the books to explain the Book!” (p. 83) Indeed, apologetics is a calamity. So much time and energy wasted on this fool’s errand, i.e., trying to lend respectability to a religion that celebrates a human sacrifice—and practices cannibalism with a straight face. Are they out of their minds?

This new Andrews book is indeed a handy guide to the great swaths of silliness in Christian theology. The footnotes, 171 of them, are a helpful portal to further research and study. This is a splendid gift for your church-going friends, at least those whom you suspect may have open minds. Andrews is blunt in wanting folks to wake up and see what’s been happening:

“…I will say with absolute conviction that Christianity itself is idiocy. The whole religion is the product of primitive times and ignorant minds…At its core, it is a fear cult shouting ‘Jesus loves you!’ against the threat of eternal torment. It is nonsense. It is offensive. It is stupid. And for two thousand years it has made believers spew nonsense designed to sound profound.” (pp. 184-185)

David Madison was a pastor in the Methodist Church for nine years, and has a PhD in Biblical Studies from Boston University. He is the author of two books, Ten Tough Problems in Christian Thought and Belief: a Minister-Turned-Atheist Shows Why You Should Ditch the Faith (2016; 2018 Foreword by John Loftus) and Ten Things Christians Wish Jesus Hadn’t Taught: And Other Reasons to Question His Words (2021). He has written for the Debunking Christian Blog since 2016.

The Cure-for-Christianity Library©, now with more than 500 titles, is here. A brief video explanation of the Library is here.

Please support us at DC by commenting on and by sharing our posts, or subscribing, donating, or buying our books at Amazon.

No comments:

Post a Comment