Why does their god play hide and seek?

We can assume that some (many?) churchgoers read the gospels, but, it would appear, without critical thinking skills fully engaged. When the devout come across Mark 14:62, does it bother them that Jesus was wrong? At his trial, Jesus was asked point blank if he was the messiah, to which he replied: “I am, and you will see the Son of Man seated at the right hand of the Power and coming with the clouds of heaven.” The main thrust of Mark’s gospel was that kingdom of his god was so close. But obviously those at his trial did not witness the arrival of Jesus on the clouds. The apostle Paul was confident too that Jesus would arrive in the sky soon. He promised members of the Thessalonian congregation that their dead relatives would rise to meet Jesus—and that he too would be there to join them (I Thessalonians 1:15-17). So Paul was wrong as well.

Paul was pumped for years by his delusions, which show up continually in his letters: he knew for sure that Jesus spoke to him in his visions. Is there any better foundation for all those “words of Jesus” in the gospels? We have no way at all to verify that the Jesus-script in Mark 14—or anywhere else—is authentic. Any historian would want to know how the author of Mark’s gospel—written some forty years after the death of Jesus—knew what was said at the trial. Was there a transcript that Mark could access? It’s very doubtful, in the wake of the very destructive first Jewish-Roman war (66-73 CE). It’s much more likely that this author created scenes as he saw fit: he was writing to promote the beliefs of his cult.

This is but one aspect of the problem of evidence that hobbles Christianity. The gospels are so highly esteemed by churchgoers, who have been raised to believe that these documents “got the story right.” But on close examination—with critical thinking skills fully engaged—it’s hard to make the case for that. There is wide consensus among devout scholars—outside of fundamentalist circles—that the gospels were written several decades after the death of Jesus. The anonymous authors never identify their sources, not even the author of Luke’s gospel, who claims in his opening verses that his stories can be traced back to eyewitnesses. But these are never identified. So historians are stumped: there is no way to verify anything we find in the gospels.

How do historians do their job? Here’s one example: in Helen Langdon’s 391-page biography of Caravaggio (1998), at the end we find a 27-page fine-print list of her sources: details about the documentation her work is based on. That’s how historians operate. But they can’t operate that way when they take up the challenge of accurately reporting the story of Jesus. There are no letters, diaries, transcripts, stenographer notes contemporaneous with Jesus that corroborate the gospel accounts. To make matters worse, these accounts are chock full of errors, contradictions, and conflicting agendas: the four gospel authors were intent on correcting each other, culminating with John, who created a very different Jesus.

They couldn’t even agree on the resurrection stories. Just read the four accounts of Easter morning, and you can appreciate the mess. I suspect the apostle Paul would have been horrified by John’s account of Doubting Thomas sticking his finger in the risen Jesus’ sword wound. No, no, no: our risen bodies will be different:

“Look, I will tell you a mystery! We will not all die, but we will all be changed, in a moment, in the twinkling of an eye, at the last trumpet. For the trumpet will sound, and the dead will be raised imperishable, and we will be changed. For this perishable body must put on imperishability, and this mortal body must put on immortality” (I Corinthians 15:51-53).

Where is the evidence to verify Paul’s claim (I’m being generous: his delusion) that the dead will be raised imperishable? Where is the evidence that John’s Doubting Thomas story (missing from the other gospels) didn’t come from the author’s imagination? —after all, he was a master at making things up! There have been memes floating around Facebook and Twitter: “This comic book is the proof that Superman is real!” “These Harry Potter books are the proof that Harry is real!” The challenge for Christians is to show how and why the gospels deserve a higher historical ranking than comic and fantasy fiction books. No, I’m not kidding. Jesus studies have been in turmoil for a long time now—totally unnoticed by the folks who attend church— because devout scholars cannot agree on which gospels texts should/can be taken seriously.

Richard Carrier has stated the problem:

“…the NT underwent a considerable amount of editing, interpolation and revising over the course of its first two centuries, and not merely as a result of transcription and scribal error, but often with specific dogmatic intent…This is not something to sweep under the rug. It makes a real difference in how we estimate probabilities. Unlike most other questions in history, the evidence for Jesus is among the most compromised bodies of evidence in the whole of ancient history. It cannot be said that this has no effect on its reliability.” (On the Historicity of Jesus, pp. 275-276)

Are we going to have any better luck with evidence for god?

I recommend a careful reading of a recent article here by John Loftus, Daniel Mocsny's Rebuttal of Paul Moser's Definitional Apologetics, Which Obfuscates the Fact That Christianity is Utter Nonsense! Loftus has repeatedly requested that Christian theologians and philosophers provide objective evidence that their god is real, can be verified by data. Moser faulted Loftus for not being precise about what constitutes objective evidence. But this is a dodge, indeed obfuscation. Since theists are those claiming that god exists, they should be fully prepared to specify the evidence they have—and show us where we can find it.

Is it too much to expect that theologians should be able to tell us where to find crucial data about their all-powerful god? This is where they fumble. “Oh, but our god commands a spiritual realm that is undetectable by science.” Our next question then must be: “How do you know this?” Where is the reliable, verifiable, objective data that backs up this claim? If they continue to fumble and equivocate, then

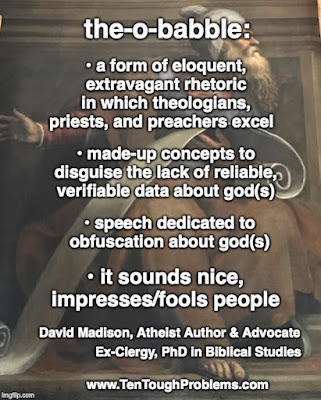

we know for sure they have retreated to theobabble, i.e., a form of eloquence designed to cover up their lack of actual knowledge. The church has thrived on theobabble for centuries.

Daniel Mocsny holds Paul Moser’s feet to the fire in the latter’s attempt to evade the call for evidence: “But most people don't demand rigorous compact definitions of things like ‘chairs’ because most people have a working understanding of what a chair is, and it's good enough. In other words there's no need to play dumb about what a chair is, and similarly no need to play dumb about what evidence is.”

“I assume Moser plies his trade from an office and never applies his thinking to solving problems in the real world - such as how might we collect raw materials and transform them into a working smartphone. Given the astronomical number of ways to combine materials at random, the overwhelming majority of which will not result in a working smartphone, presumably Moser will agree that for scientists and engineers to manage this trick billions of times with a very low failure rate, they must have rules for evidence that are stupendously good.”

“It's trivial to show that no religion has evidence as strong as either the law or science demands. No religion can prove its supernatural claims in a legitimate court of law, and no religion relying on faith builds anything like a smartphone. What has any religion produced besides words, and manipulating people? There is nothing to suggest that any religion has the kind of deep insight into reality that enables science to work actual near-miracles.”

Author Robert Conner (The Death of Christian Belief, The Jesus Cult: 2000 Years of Last Days, Apparitions of Jesus: The Resurrection as Ghost Story) commented on the Mocsny article:

Embarrassed by the lack of science-based evidence for their deity, theologians and clergy commonly resort to “rounding up the usual suspects” (that classic line from the movie Casablanca), e.g., revelation through scripture, visions, prayer-based insights about god. But these all fail to deliver: Christianity has splinted into thousands of conflicting denominations because—among other things—they disagree about the god, based on the Bible itself. And, of course, the “inspired” scriptures of Mormons and Muslims are rejected. Visions too have yielded vastly different images of god(s) and saints; Protestants commonly ridicule Catholic vision claims. Christians have prayed endlessly to their god, but hold very different views on what god wants and expects.

Isn’t it so obvious that an all-powerful, competent, wise, caring god could have cleared up this mess a long time ago? “God can do anything!” devout believers claim. “Well, good, have him say Hi!” Let the evidence be clear and obvious. The gospel resurrection story itself fails by this standard. Why didn’t the resurrected Jesus show up at Pilate’s house on Easter morning? Why didn’t he appear to Caesar himself?

“Better still, the resurrected Jesus could have gone on a Worldwide Resurrection Tour with stops in China and every city, town, and village in the world.” (Tim Sledge, Four Disturbing Questions With One Simple Answer: Breaking the Spell of Christian Belief, p. 63)

Especially since the all-power Christian god gets really furious when humans don’t obey and worship him, it is very strange that he has failed so miserably when it comes to the presentation of evidence.

David Madison was a pastor in the Methodist Church for nine years, and has a PhD in Biblical Studies from Boston University. He is the author of two books, Ten Tough Problems in Christian Thought and Belief: a Minister-Turned-Atheist Shows Why You Should Ditch the Faith, now being reissued in several volumes, the first of which is Guessing About God (2023) and Ten Things Christians Wish Jesus Hadn’t Taught: And Other Reasons to Question His Words (2021). The Spanish translation of this book is also now available.

His YouTube channel is here. At the invitation of John Loftus, he has written for the Debunking Christianity Blog since 2016.

The Cure-for-Christianity Library©, now with more than 500 titles, is here. A brief video explanation of the Library is here.

No comments:

Post a Comment