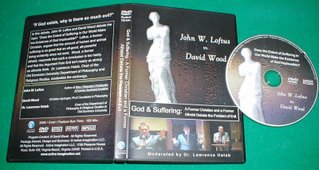

Since I have now posted my opening statement from the debate I had on October 7th with David Wood on the problem of evil here, readers can pretty much compare what I said with David's review of our debate seen here for themselves. I was initially going to go through his review in several more in-depth parts, but I've decided instead to respond to the objections he offered in his review in just one final Blog entry--this one--and be done with it. People seem to be tiring of this ongoing debate, and so am I. This means my response here will be much briefer and less in-depth than I had initially planned to write.

I'm looking at this world and asking whether or not God exists, while David already believes God exists and is trying to explain why there is intense suffering in this world given that prior belief. The God-hypothesis may be able to explain why this world is the way it is (with a lot or argumentation), but that's a far cry from this world being the one we would expect if there was a good God, and these two different perspectives make all the difference in the world.

The first thing to say about David's review is that he presented several arguments in his review that he never presented that night in our debate. That's why I'd like to deal with them here, along with the others he did mention that night.

Concerning the the armlessness of the Venus de Milo statue. David, tell me what sculpturer would create a woman and then chop off her arms? What realist sculpturer would create a statue without arms? Answer the question, my friend. What reasons can you offer me for this? It’s precisely because there are no arms that I do not see a sculpturer at all. To me it would be an unusual rock formation. That best explains what I see. [As far as the design argument itself goes, I'll pass on this for now, and as far as the supposed mythical fall of Adam and Eve goes, I'll pass on that too].

David Wood:

"To put the matter differently, a theist could say, “I have no clue why God allows evil, but I’m going to believe that he has his reasons anyway,” and he would be no worse off than the atheist when the latter says, “I have no clue how life could have formed on its own, but I’m going to believe it anyway.” Nevertheless, since theists can offer at least some plausible reasons for God to allow suffering, they are on much better ground than atheists."

John Loftus:

As I recently said, arguments for the existence of God, are not strictly relevant to our specific debate issue, since I already hypothetically granted you for the purpose of the debate that your God exists. Think about this. The question I was addressing can be accurately phrased like this: Given that your omni-God exists, then why is there intense suffering in this world? And my conclusion is that intense suffering in this world makes the existence of your omni-God implausible (or improbable), regardless of the arguments for the existence of God, which provides for you the Bayesian background factors leading you personally to believe despite the extent of intense suffering in this world. I was arguing from evil, not from the non-existence of your omni-God hypothesis. Just read Howard-Snyder's book called The Evidential Argument From Evil, to see this. The book does not contain one single argument for the existence of God, either pro or con, except as it relates to the problem of evil itself. I see no chapters in it on the design or cosmological or ontological arguments, for instance. The arguments were strictly dealing with how the omni-God hypothesis relates to the issue of suffering. If that hypothesis is true, then is this the kind of world we should expect? The debate was (and is) over whether the evidential argument from evil makes the omni-God hypothesis implausible (or improbable) on its own terms.

David Wood:

"I talked about an incident in which my oldest son, then a year old, needed four shots. I had to hold him down while the doctor stabbed him repeatedly with a needle. Could my son comprehend why I was apparently helping a person stab him? No. My reasons were beyond his comprehension."

John Loftus:

But where were you when your oldest son got sick? If you could keep him from being sick then wouldn't a good father would do it? Sure he would. God is like the father who allows a child to get sick in the first place. A more comparable case would be if a surgeon operates on a person in order to transplant a kidney to another person against the wishes of that involuntary donor. Or a dentist who extracts the teeth of someone without any anesthetic, or legislators who seek to raise the standard of living in an underdeveloped country by killing off half the population when their standard of living could‘ve been improved by using better agricultural methods.

David Wood:

(1) If God does not exist, then objective moral values do not exist.

(2) Objective moral values do exist.

(3) Therefore, God exists.

John Loftus:

1) There are both deontological and teleological views of objective morals that do not depend upon God. Besides, the divine command theory is in such disrepute today that no one defends it that I know of.

2) Michael Shermer makes an interesting argument in his book, The Science of Good and Evil (Henry Holt, 2004), that “morality exists outside the human mind in the sense of being not just a trait of individual humans, but a human trait; that is, a human universal.” According to him we “inherit” from our Paleolithic ancestors our morality and ethics, then we “fine-tune and tweak them according to our own cultural preferences, and apply them within our own unique historical circumstances.” As such, “moral principles, derived from the moral sense, are not absolute, where they apply to all people in all cultures under all circumstances all of the time. Neither are moral principles relative, entirely determined by circumstance, culture and history. Moral principles are provisionally true—that is, they apply to most people in most cultures in most circumstances most of the time.” [pp. 18-23].

David Wood:

"As it turns out, atheists who use the argument from evil do indeed appeal to objective moral values, and they do so on two different levels. One, by arguing that suffering is bad or evil, they’re appealing to some objective standard of good and evil. If the atheist replies here that suffering isn’t really evil, then how does what is not evil conflict with God’s goodness? Two, by saying what God must and must not do, atheists are claiming that there are moral laws that even God would have to follow. Hence, in both cases the atheist must appeal, directly or indirectly, to moral values that transcend humanity."

John Loftus:

This whole issue is a “pseudo-problem” when it comes to why your God allows intense suffering in our world. The word “evil” here is used both as a term describing suffering and at the same time it’s used to describe whether or not such suffering is bad, and that’s an equivocation in the word’s usage. The fact that there is suffering is undeniable. Whether it’s bad is the subject for debate. I'm talking about pain...the kind that turns our stomachs. Why is there so much of it when there is a good omnipotent God based on YOUR OWN BELIEFS ABOUT THE MORAL QUALITIES OF YOUR GOD? [Sometimes capitalizing things helps to emphasize them. ;-)]I’m arguing that it’s bad to have this amount of suffering from a theistic perspective, and I may be a relativist, a pantheist, or a witchdoctor and still ask about the internal consistency of what a theist believes. The dilemma for the theist is to reconcile senseless suffering in the world with his own beliefs (not mine) that all suffering is for a greater good and that this world reflects a perfectly good God. It’s an internal problem for the theist.

Just tell me this David...what moral attribute did your God exhibit when he did nothing to avert the 2004 Indonesian tsunami? You tell me! You do realize that the more power a person has to stop evil the more responsibility he has to stop evil. No one imprisoned in any gulag had the power to stop the gulag system itself, so they cannot be blamed for its existence, and I may not have the power to stop a gang of thugs from beating a person to death. But your God is omnipotent. With just a snap of his fingers he could have saved over a quarter of a million people, and not one of us would ever have known he stopped it, precisely because it didn't happen.

David Wood:

"(1) John argued that giving us free will is like giving a razor blade to a child. No it’s not. Nothing good is going to come from giving a razor blade to a child."

John Loftus:

Yes it is. Razor blades can be used for good purposes by people who know how to use them, like scraping off a sticker from a window, or in shaving. That’s because adults know how to use them properly. We could give an adult a razor blade. We cannot give a 2 year old one, for if we did we would be blamed if that child hurts himself. Just like a younger child should not be given a license to drive, or just like a younger child should not be left unattended at the mall, so also if God gives us responsibilities before we can handle them then he is to be blamed for giving them to us, as in the case of free will.

David Wood:

"(2) John argued that God should have given us stronger inclinations to do what’s right. I’m not sure how this would differ from taking away our free will."

John Loftus:

This is not an all or nothing proposition here. I argued that if God made us with an aversion against wrongdoing just like we have an aversion against drinking motor oil, then it would cut down on us drinking motor oil. We could still do it, of course. Still this is just an analogy. I offered many examples of what God could've done.

David Wood:

"(3) What John has in mind is that God should limit our ability to, say, harm one another. But what would this look like? God takes away our ability to build knives, so we can no longer cut each other. But now we can’t cut anything at all. Or perhaps God takes away my fists so that I can’t hit my neighbor. It seems, however, that he would need to remove my hands. How could I type a letter?"

John Loftus:

God has many other means at his disposal here, if we concede for the moment the existence of this present world: One childhood fatal disease or a heart attack could have killed Hitler and prevented WWII. Timothy McVeigh could have had a flat tire or engine failure while driving to Oklahoma City with that truck bomb. Several of the militants who were going to fly planes into the Twin Towers on 9/11 could’ve been robbed and beaten by New York thugs (there’s utilitarianism at its best). A poisonous snakebite could’ve sent Saddam Hussein to an early grave averting the Iraq war before it happened. The poison that Saddam Hussein threw on the Kurds, and the Zyklon-B pellets dropped down into the Auschwitz gas chambers could have simply “malfunctioned” by being miraculously neutralized (just like Jesus supposedly turned water into wine). Sure, it would puzzle them, but there are a great many things that take place in our world that are not explainable. Even if they concluded God performed a miracle here, what’s the harm? Doesn’t God want us to believe in him?

It does absolutely no good at all to have free will and not also have the ability to exercise it. Our free will is limited by our age, race, gender, mental capacity, financial ability, geographical placement, and historical location to do whatever we want. I could not be a world-class athlete even if I wanted to, for instance. Therefore, we do not have as much free will as people think. My point was that if free will explains some of the intense suffering in this world when we already have limited choices anyway, then there should be no objection to God further limiting our choices when we seek to cause intense suffering in this world, and doing so in the reasonable ways I’ve suggested. My point is that the theist believes God can do this just as he purportedly did when he hardened Pharaoh’s heart against Moses.

David Wood:

"Another inconsistency related to John’s position is that he seemed to be arguing (1) that humans are so bad that God shouldn’t have created us, and (2) that we’re so good that God shouldn’t let us suffer. I think he needs to pick one or the other and stick with it. Part of John’s argument needs to be jettisoned."

John Loftus:

No. I’m arguing that humans should not have to suffer so much if there is a good God, precisely because God is supposed to be good. If God created us to suffer so much, then he shouldn’t have created us. It’s a problem for God and how he should treat his creatures, and he should show more love than he does if he is perfectly good. It doesn’t have anything to do with human goodness. It has all to do with God’s goodness.

David Wood:

"Yet another inconsistency that emerged in the debate and in John’s review is that John demands that theists account for all the intense suffering in the world, and all of the various kinds of evil in the world. But would an atheist ever accept such a high burden of proof for his own position? Of course not."

John Loftus:

I was merely asking David to account for one category of suffering, intensive suffering. Parasites kill one person every ten seconds, for instance. A theodicy is supposed to do what I ask, if it is to be considered a theodicy in the first place. It must explain why there is so much evil, and account for every category of evil. Since neither the theist nor the atheist can totally and rationally account for their respective brute facts (the theist cannot account for something that has always existed, and the atheist cannot fully account for why something popped into existence out of nothing) this is a wash. But the theist cannot believe in truly gratuitous evil—pointless evil. Therefore the theist must offer reasons that suggest there is no gratuitous evil, for if he admits there is one such evil, he no longer can believe in a perfectly good God. Therefore he must account for the most horrendus categories of evils in our world. Several major theists no longer even try to offer a theodicy. They admit it cannot be done.

David Wood;

"Loftus quotes Andrea Weisberger, who says that if free will is so important, we should possess it perfectly. But what can she mean here?"

John Loftus:

She means that if we did have the ability to do anything there would be much more evil, so even a theist doesn’t want us to have this kind of freedom. If free will is such a good thing, then why would the theist be the first one to say it isn’t?

David Wood:

"Thus, John blames God for racism. If God had only created one race, John says, then there would be no racism. But let’s keep going…..What does John’s view entail? A world without diversity, filled with men made by a single cookie-cutter. True, it would be a world without racism. But I’m not sure it would be a better world."

John Loftus:

Racism is a huge area of conflict among humans, and easily could’ve been eliminated if God made us all one color of skin, so he should have, even if we may have still had conflict because of other differences. There would have been no race based slavery in the South. No one suggested God should do away with all diversity. Just obvious cases of it. This is not an all or nothing proposition.

David Wood:

"(4) Now I do understand when someone asks, “Well, why didn’t God stop Hitler?” Even if free will is important, we’d be inclined to draw a line somewhere. So why doesn’t God intervene more than he does? Well, if we follow this mode of thinking through to its logical conclusion, we find that this sort of interference by God would destroy morality."

John Loftus:

No this would not! You’re making an inference that it’s an all or nothing. Either God stops all pain caused by free will or he does practically nothing. That’s a false dilemma. I think it’s obvious that he should’ve stopped the tsunami and the 9/11 attacks.

David Wood:

"If God brings things about through our free choices, without interfering, then God may allow horrible atrocities because they play an important role in future events. Think about the Holocaust. It was awful. But when it was over, the nation of Israel was reinstated in the Middle East."

John Loftus:

As Dr. Hatab asked, what about the Palestinians? “A perfectly good God would not wholly sacrifice the welfare of one of his intelligent creatures simply in order to achieve a good for others, or for himself. This would be incompatible with his concern for the welfare of each of his creatures.” [William P. Alston in The Evidential Argument From Evil, p. 111]. Therefore, the theist has the difficult task of showing how the very people who suffered and died in the Nazi concentration camps were better off for having suffered, since the hindsight lessons we’ve learned from the Holocaust cannot be used to justify the sufferings of the people involved.

David Wood:

"Second, I don’t see how an atheist can sincerely say that God should go around killing people. Why not kill anyone who’s going to do something wrong? Now John might say, “Well, God should draw the line exactly where I would draw it.” But if he says that, then he’s just saying that if God exists, he should be just like John Loftus, with John’s opinions and views."

John Loftus:

I’m not talking about an all or nothing proposition here. The fact that the giver of life does not protect innocent life by killing more evil people is what I question.

David Wood:

"Third, we shouldn’t forget that God has given us the ability to deal with people like Hitler. People like Hitler, Stalin, Pol Pot, and others arise, and we can either fight them and fix the situation, or we can sit back and do nothing. But God hasn’t left us helpless. When evil prevails, it’s our fault for letting it prevail."

John Loftus:

We cannot do it alone. How is a 10 year old going to keep Pol Pot’s men from raping and dismembering her?

David Wood:

"(5) John argued that suffering leads people away from God. He was responding to my Wizard of Oz theodicy. Christianity is spreading most rapidly in places where there has been tremendous suffering."

John Loftus:

This whole argument reminds me of Jeff Lowder’s comment: “It’s like saying in order to get my wife to love me I have to beat the crap out of her.” [Lowder/Fernandez debate on Theism vs Naturalism]. In an online article titled Human Suffering and the Acceptance of God by Michael Martin, Martin argues against such an idea. He questions their statistical facts, of course, but then continues to argue that: “1) If God's aim was to have the maximal number of people believe in God, as Craig has argued, He has not been successful. Billions of people have not come to believe in the theistic God. 2) There are many better ways God could have done to increase belief in Him. For example: God could have spoken from the Heavens in all known languages so no human could doubt His existence and His message. God could have implanted belief of God and His message in everyone's mind. In recent time God could have communicated with millions of people by interrupting prime time TV programs and giving His message. 3) Why is there not more suffering, especially in America, since unbelief is on the rise? 4) There is also the ethical issue. Why would an all good, all powerful God choose to bring about acceptance in this way since God could bring about belief in Him in many ways that do not cause suffering? Not only does suffering as a means to achieve acceptance conflict with God's moral character, it seem to conflict with His rationality. Whether or not suffering is a cause of acceptance is one thing. The crucial question is whether it is a good reason for acceptance.”

David Wood:

"(6) John says that soul-building is pointless, since virtue won’t play a role in heaven. I’m not sure that virtue won’t play a role in heaven, but even if it doesn’t, developing virtue certainly affects the soul, and this effect is positive. But besides all of this, it never occurs to John that some things are good in themselves. It is good to be patient, or courageous, or temperate, regardless of whether these things play a role in eternity."

John Loftus:

I do not accept a deontological ethic. I am a consequentialist standing firmly in the teleological traditon of ethics, not the duty centered traditon. David needs to show how these particular virtues affect the soul, and if he can do that then he can show that these virtues are intrinsically good. Until then, he cannot. He needs to offer some suggestions here, and I don’t see any, especially when he now claims there will be no morality in heaven. If there is no morality in heaven and no free will in heaven, then there is absolutely no reason why God couldn't have just created us all as amoral non-free creatures there in the first place.

And there is the additional problem of free will in hell. Theists typically claim that people in hell continue in their rebellion against God and so the "doors of hell are locked from the inside." Why this difference? Those who are saved are rewarded for their tortures here on earth by the removal of their free will to make moral choices, but if those who are damned have their free will taken away, then they too could be brought up to heaven. And if free will is such a good thing, as our debate clearly revealed the difference here with us, then why isn't it such a good thing in the end with believers in heaven?

David Wood:

"Suppose you’re walking down the street, and you find a purse full of money, but there’s a police officer standing there. Now all of us would do the right thing. We’d all return the purse. But we’d be returning it because there was a police officer standing there, not because it’s the moral thing to do."

John Loftus:

Even if this were always the case, which is not what I propose, if God was interested in our morality and he judges our hearts, then even if there is a police officer stopping us every time we want to do wrong, then God knows we wanted to do wrong, which is all that an omniscient being needs to see in order to judge us.

David Wood:

"(7) John said in his review that I never responded to the problem of animal suffering. I’ll admit that, given the extent of human suffering in the world, I’m far less concerned about animal suffering. However, I did give a brief response during the debate. Pain serves an important biological role. If the atheist thinks that God should take away an animal’s ability to feel pain, I hope he’s ready for the consequences. If cats didn’t feel pain, they would be extinct by now. When Fluffy jumps on a hot stove, pain tells her to get off the stove because the stove is harmful. As such, Fluffy should thank God for pain."

John Loftus:

I was talking specifically about the law of predation. The spider will wrap its victim up in a claustrophobic rope-like web and inject a fluid that will liquefy its insides so he can suck it out. The Mud wasp will grab spiders and stuff them into a mud tunnel while still alive, and then places its young larva inside so they can have something to eat when they hatch. The cat will play with its victims until they have no strength left, and then will eat them while still alive. The boa constrictor will squeeze the breath out of its victims crushing some of its bones before swallowing it. Killer whales run in packs and will isolate a calf and jump on it until it drowns in salt water, whereupon the bloody feeding frenzy begins. The crocodile will grab a deer by the antlers and go into a death spiral breaking its neck and/or drowning it before the feeding frenzy begins. Nature is indeed “red in tooth and claw.”

All creatures should be vegetarians. And in order to be sure there is enough vegetation for us all, God could’ve reduced our mating cycles and/or made edible vegetation like apples trees, corn stalks, blueberry bushes, wheat and tomato plants to grow as plenteous as wild weeds do today. Even if Christians believe we were originally created as vegetarians, why should animals suffer because of the sins in Noah’s day (Genesis 9:3)? What did animals do wrong?

God didn’t even have to create us such that we needed to eat anything at all! If God created the laws of nature then he could’ve done this. Even if not, since theists believe God can do miracles he could providentially sustain us all with miraculously created nutrients inside our biological systems throughout our lives, and we wouldn’t know anything could’ve been different.

David Wood:

"If I know John by now, I think he would respond that if animals must experience pain, then God shouldn’t have created them. This is one of the greatest differences between John and me. I think it’s better to exist, even if something is going to suffer."

John Loftus:

There is no good reason for God to have created animals at all, especially since theists do not consider them part of any eternal scheme, nor are there any moral lessons that animals need to learn from their sufferings. Does David really think it's better to exist with terrible suffering than never to exist at all? Childhood leukemia? Childhood rape? Spina bifida? The children who lost their lives during the Spanish Influenza of 1918? Better for whom? Some babies die shortly after they are born, while Jesus said that "many" will end up in hell. Is that better? More importantly, does this reflect well on the whole notion of a perfectly good God?

David thanks for the exchange. You have a very bright mind, and I wish you all of the very best in life.

Enlarge it here

Enlarge it here